THE Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 was a turning point in Irish-British relations.

It didn’t bring peace immediately but represented the first major advance on the road to a peaceful resolution of the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

The Sunningdale Agreement in 1973, which attempted to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive, might have worked, but was extinguished by unionist opposition, a loyalist general strike, and widespread violence.

The Anglo-Irish Agreement, on the other hand, although not bearing immediate fruit in terms of a cessation of violence, was a forerunner of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

The Agreement signed in November 1985 by Taoiseach Dr Garret Fitzgerald and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher included two crucial elements: for the first time since partition, the Irish government had a right, based in international law, to have a significant input into the processes of the government of Northern Ireland.

In exchange, it confirmed that there would be no change in the constitutional position of Northern Ireland unless a majority of its people agreed to join the Republic.

These were both momentous steps.

Events leading up to the agreement could scarcely have been less propitious. The hunger strikes had caused relations between Charles Haughey and Margaret Thatcher to deteriorate significantly — exacerbated by taking Argentina’s side in the Falklands War

The IRA’s campaign in Britain was ongoing, with Mrs Thatcher herself the target in the Brighton hotel bombing of October 1984.

But by 1985 Garrett FitzGerald was Taoiseach, and powerful US pressure was being applied for a solution to be found.

Against this backdrop, talks about sorting out the imbroglio began.

The book

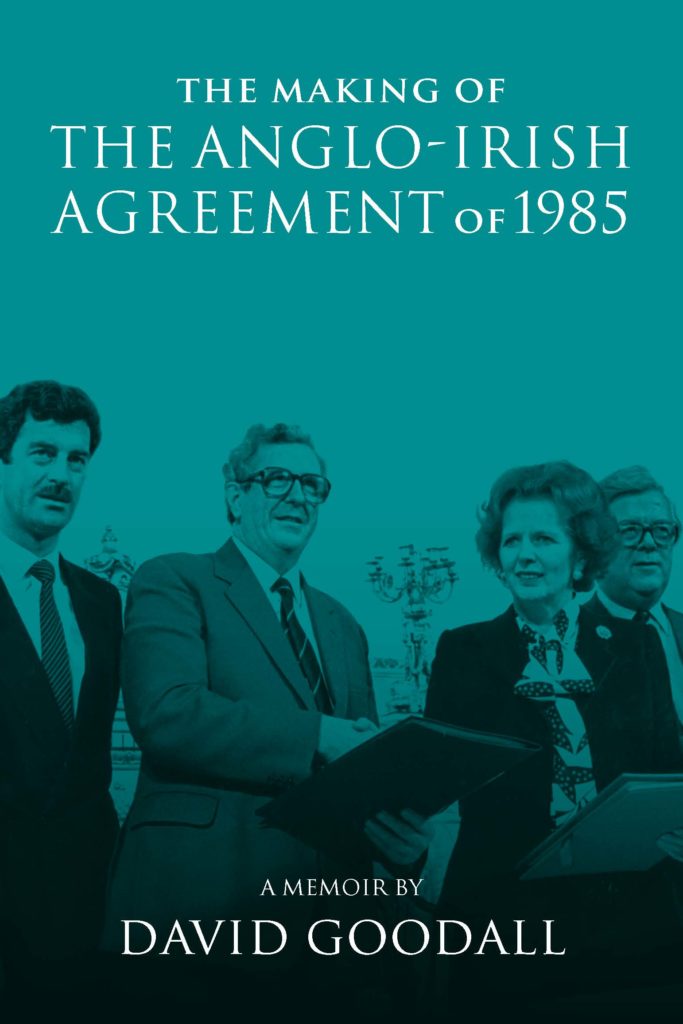

The Making Of The Anglo-Irish Agreement Of 1985 — A Memoir by David Goodall, edited by Frank Sheridan gives, for the first time, an insider’s account of the protracted, tense and ultimately fruitful negotiation.

Goodall kept a personal journal throughout the negotiations, but one that has, until now, remained under personal and official embargo.

His elegantly written, highly personal account is gripping and frequently astonishing it its frankness. It is, in short, fascinating.

Goodall captures the nerve-wracking fluctuations in negotiations between the two sides, as they tottered continuously between collapse and survival. He recounts the dramatic exchanges between the two sides.

He also talks about the internal tensions on his own side: those between the Prime Minister and her own negotiators, as well as those between the Northern Ireland Office and the Cabinet Office. These were as bitterly fought as the main negotiations.

The talks proceeded under the cloud of Margaret Thatcher’s dislike and distrust of Irish nationalism.

At the first meeting at Chequers between Taoiseach Garret Fitzgerald and the Prime Minister, Goodall notes that Mrs Thatcher was ‘aggressively negative’.

Mrs Thatcher’s ignorance of Irish affairs, or any grasp of the complexity of a problem that was Britain’s making, is highlighted in the memoir.

In one astounding revelation Goodall details how she suggested moving the entire nationalist population of Northern Ireland to the Republic.

He writes: ‘The Prime Minister asked why arrangements could not be made to transfer those members of the minority community who did not wish to remain under British rule to the Republic.

‘After all, she said, the Irish were used to large-scale movements of population.

‘Only recently there had been a population transfer of some kind. At this point the silence round the fire became transfused with simple bafflement.

‘After a pause, I asked if she could possibly be thinking of Cromwell.’

“Cromwell: of course.”

“Well, Prime Minister, Cromwell’s policy was known as ‘To Hell or Connaught’ and it left a scar on Anglo-Irish relations which still hasn’t healed.”

The idea of a population transfer was not pursued.

Sense was eventually drilled into Mrs Thatcher, partly due to the influence of Garret FitzGerald’s belief in the treaty, partly through heavy US pressure, and partly because — no matter what you think of her — the UK prime minister was overall an astute politician.

She could see the way ahead required compromise.

Goodall’s memoir describes how, with the persistence and patience of negotiators on both sides that an almost improbable conclusion was reached — the treaty was signed.

Sir David Goodall

Sir David Goodall, who died in 2016 aged 84, was one of two key negotiators on the British side. He was a devout and well-connected Catholic with family roots in Co. Wexford — he was always very proud of his Irish heritage.

Goodall was educated at Ampleforth College, one of the world’s foremost Catholic boarding schools. He finished his academic studies at Oxford.

With a first-rate analytical mind, Goodall was well qualified to provide insight and clarity into the colonial disarray that was Northern Ireland.

The editor, Frank Sheridan

Frank Sheridan is a retired Irish diplomat. Earlier in his career he served in the office of Garret FitzGerald when he was Foreign Minister, and also served as Private Secretary to Foreign Minister Peter Barry during the later stages of the negotiation of the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985.

The contributors

There are significant contributions from other interested parties including

Maurice Manning, Chancellor of the National University of Ireland who publish the memoir

Morwenna Lady Goodall, Sir David’s wife and very much an active comentator

Stephen Collins, columnist at the Irish Times

Michael Lillis, diplomatic adviser to Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald, and David Goodall’s opposite number on the Irish negotiating team

Charles Powell, Mrs. Thatcher’s influential Private Secretary during the negotiations

Robin Renwick, foreign policy adviser to Mrs. Thatcher and British Ambassador to the USA

Extracts from the book

Sir John Hermon, RUC Chief Constable: “As part of the process of educating myself about the problems we were dealing with, I had lunch on 10 January 1984 with Sir John Hermon, the Chief Constable of Northern Ireland.

“I had heard him speak at the BIA conference and been impressed with his forceful and articulate answers to difficult questions; but I expected him to be dour and cautious in talking to me.

“In the event he was quite remarkably frank. In the long term, he thought the unification of Ireland in some form or other was inevitable, and he was strongly against any further integration of the Province into the United Kingdom.

The Anglo Irish negotiating team, with David Goodall pictured back row, far left

The Anglo Irish negotiating team, with David Goodall pictured back row, far leftPrime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s message to the Taoiseach before the signature of the Anglo-Irish Agreement: …”We are embarking on something entirely new and exciting in the hopes and possibilities it contains for making life better for all the people of Northern Ireland.

“We both know that it is not going to be all plain sailing. I am sure that as the new arrangements bed down during the corning months we shall need on both sides patience and forbearance, as well as the understanding and good will that have been brought up during these long months of negotiation.

“They will be forthcoming on our side, I can assure you.”

The Making Of The Anglo-Irish Agreement Of 1985 — A Memoir by David Goodall is published by the National University of Ireland and distributed by Four Courts Press