Two businesswomen greeting each other with foot bump during COVID-19 pandemic in office. People who … [+]

Younger investors often find it difficult to focus on saving for retirement, let alone consider the tax implications of different vehicles. Life is hectic in the early earning years when job mobility is high, new families are formed and major decisions like purchasing a house or deciding where to live absorb all the attention. It may also seem that what they can put aside is not enough to merit close attention.

Yet, it is precisely during those early years when the impact of their savings strategies will be strongest. It is a well-established fact that the sooner someone starts putting any amount of money on the side, the better off they will be later, when how much they saved becomes a more important part of their lives.

How much they can put away is certainly important. The more, the better, and “free money” such as employer contributions to retirement accounts must always be maximized. But even small amounts can turn into big sums in the long run.

The tax efficiency of the savings strategy is also an important consideration. The two most common vehicles, outside of employer-sponsored programs, are Roth IRAs and Traditional IRAs. The difference between the two is that contributions to Traditional IRAs are not taxed until the saver starts taking money out of the account, while contributions on Roth IRAs are taxed upfront.

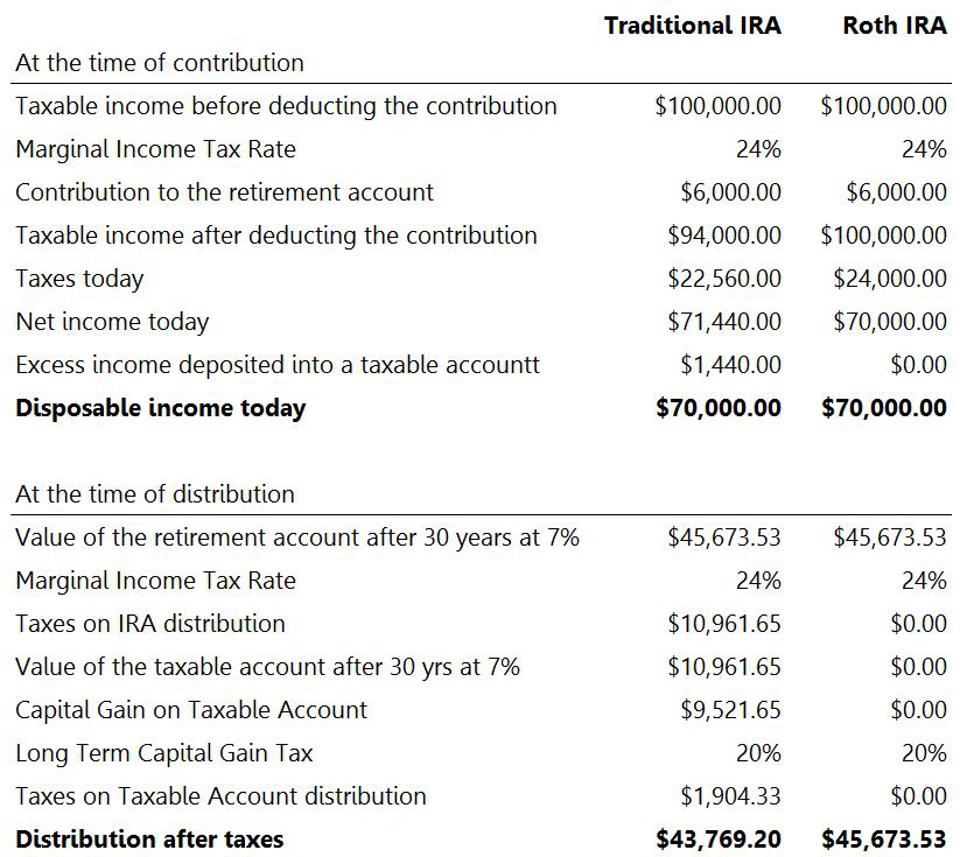

Assuming a constant marginal tax rate, a Roth IRA is a better savings vehicle. The table below explains why:

A Roth IRA can be better than a Traditional IRA if the marginal tax rate of the saver is the same at … [+]

In this scenario, the taxpayer can contribute either to a Traditional IRA or to a Roth. Choosing the former offers a tax deduction at the time of contribution, while choosing the Roth does not. In order to make the comparison meaningful, the tax savings of the IRA contribution go into a taxable account so that the disposable income on the contribution year is the same for both strategies.

As the table shows, although the traditional IRA plus the taxable account grow to be much larger than the contribution to the Roth, the taxes due at the end more than eliminate the surplus.

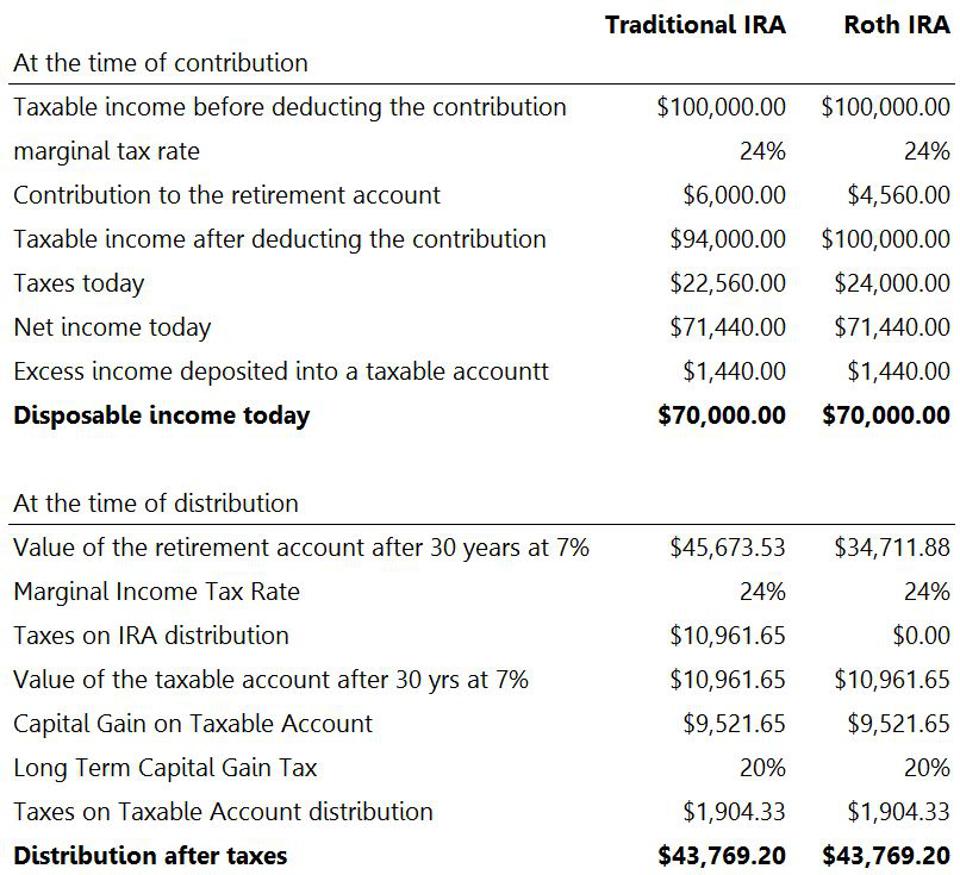

Notice that this is not the same as making a contribution to the Roth that is adjusted down by the tax rate. In that case, both would be equivalent because the lower Roth balance means that the tax-free gains over 30 years will be lower. The table below describes such scenario. Just to make the disposable income the same as in the previous case we assume that there is a deposit into a taxable account for both strategies, but doing this does not change the fact that both are equivalent strategies – if the tax rate remains the same.

Contributing less to a Roth IRA to adjust for the Traditional IRA tax deduction makes both … [+]

Since young earners tend to be at lower marginal tax brackets when they contribute than when they start withdrawing (59 ½ years of age), Roth IRAs offer a further benefit. Contributing when the marginal rate is 22% and withdrawing when it is at 24% widens the difference to $42,348.50 for the Traditional versus $45,673.53 for the Roth.

In practice, it is impossible to predict the tax rate 30 or 40 years down the road. Not only tax rates can be very different from today, but also there is no way of knowing what the taxable income will be for the taxpayer in retirement that will determine that tax rate. The filing status could change from single to married, filing jointly or separately. It is also impossible to say decades ahead whether the combination of Social Security, required minimum distributions and passive income would mean a higher or lower bracket for the taxpayer.

Given the mounting deficits the U.S. is currently experiencing, a recent common refrain has been that taxes are sure to go up. However, this is not at all certain for someone who starts saving today and who will not start withdrawing for decades.

Consider this: Just like today, Americans were very concerned about the fiscal deficit back in the 1980s, when it reached 5.7% of GDP, its worst level in almost 40 years. Few would have predicted correctly at the time that the highest tax bracket would not rise but instead drop from 50% then to 37% today (and even lower in the intervening period) or that by the late 1990s the country would have enjoyed its largest budget surplus in decades – only to sink again into deficit later on. In other words, today’s deficits are a very poor predictor of tax rates thirty years from now.

People have to make decisions under significant uncertainty, and tax policy is just as unpredictable as the stock market. One reasonable assumption is that tax rates would remain progressive (i.e higher incomes will be taxed at higher rates). This means that early savers, which tend to be at the foot of their income ladder, should start by making contributions to their Roths as long as they are in the lower tax brackets and expect their incomes to go up. Above certain income levels, taxpayers should switch to Traditional IRA contributions.

There are complications to this. Contributions to Traditional IRAs have income limits when the taxpayer also benefits from an employer-sponsored savings plan. Also, Traditional IRAs can be converted to Roth IRAs at strategic times (for instance, right after a big market decline) that can result in lower conversion taxes. Because of the complexities involved, a financial advisor can be very helpful in plotting a course of action that effectively incorporates the tax implications of different savings strategies.