With taxes on the wealthy seemingly on track to increase under President Joe Biden, many affluent investors have been rushing to reconfigure their retirement strategies to lessen a financial blow in the future.

But the strategy of choice — shifting money from a traditional IRA or 401(k) into a tax-advantaged Roth plan — involves a surprisingly nuanced calculus. Factors that can make the move a good idea or a bad one include an investor’s age, income needs, earning potential, future retirement location and method for paying the up-front tax bill that comes with a conversion.

On the tax front, arguably the toughest factor, one prominent wealth planner has a secret weapon for clients that she calls “the greatest thing for them and their heirs.” The advisor, Laila Pence, adds that “we do think there’s going to be some tax changes coming, so we’re trying to take advantage this year for most clients we serve to reduce their estate taxes.”

Bloomberg News

Roth IRAs are funded with money on which taxes have already been paid. Their annual contribution limits are low — $6,000, plus an extra $1,000 for those over 50 — and investors have to earn below $140,000 ($208,000 if married). Hold onto the plan for at least five years, and you can generally withdraw your earnings free of tax. But if you’ve had the account less than five years and are under age 59 ½, you face a 10% penalty and income tax on the withdrawal.

By contrast, a traditional IRA is built with pre-tax dollars that appreciate over time. Investors pay ordinary rates on withdrawals. While there are no income limits on who can own one, the contribution limits are the same as for a Roth. Putting in money creates a tax deduction for those making under $76,000 (up to $125,000 for married people,depending on which spouse participates in the plan.)

Lock it in

Why are advisors urging clients to ditch their regular IRAs for a Roth? To lock in today’s lower rates.

The Biden administration wants to nearly double the capital gains rate on people making more than $1 million. (It’s currently 23.8%, including the Affordable Care Act’s 3.8% surcharge.) It also wants to raise the top individual rate to 39.6% from 37%, which currently hits income above $523,601 for individuals ($628,301 for married couples).

Bloomberg News

Traditional IRAs are still a gorilla of the retirement marketplace, with around $11 trillion in assets, according to Cerulli Associates. But Roth IRAs are the fastest-growing segment of the IRA market, with assets topping $1.2 trillion last year, three quarters held by investors age 60 or older.

IRS rules don’t limit how much of a traditional IRA can be converted to the Roth variety. The converted amount appreciates over time, and withdrawals are tax-free. The hitch: when converting, you have to pay the taxes due on the traditional IRA’s appreciation at the time.

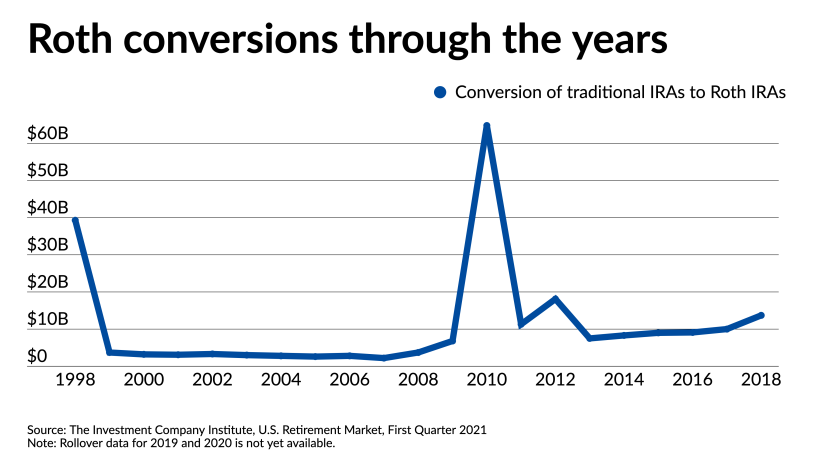

Unlike traditional IRAs, Roth plans don’t have required minimum distributions once an investor hits age 72. RMDs are taxable, so transferring money to a Roth can lower an investor’s annual tax bill and move money out of her estate, leaving more money for heirs. Conversions became possible in 1998 under IRS rules. They spiked in 2010 when income limits were scrapped and investors got two years to pay the tax due.

Today, a Roth IRA conversion is “a better tool to lower one’s taxable estate and create tax savings,” says Jon Ekoniak, a partner and CFP at Bordeaux Wealth Advisors in Menlo Park, California. Every dollar moved out of an estate saves 40 cents in estate tax for investors worth more more than $11.7 million (more than $23 million for couples).

Biting the tax bullet

So what’s the biggest challenge for investors? Convincing them to bite the conversion tax bullet up front. Which brings us back to Pence, the president of Pence Wealth Management in Newport Beach, California, affiliated with giant brokerage-advisory firm LPL Financial.

Pence, a CFP and top-ranked Barron’s advisor for six years, uses a sort of Jedi mind trick with older affluent clients to handle the traditional aversion to taxes. Instead of having clients grudgingly write a check to the IRS for the tax immediately due on the converted amount, she urges them to use what’s left over, after tax, from an RMD from a traditional plan to foot the tax bill. “Mentally, it’s a lot easier,” she says. Because these wealthy clients don’t need RMD money to live on, “they’re much more likely to do a conversion” if the tax money comes from something other than their bank account.

Bloomberg News

She cites an older client with a $3 million traditional IRA who was initially reluctant to convert. The client had plenty of cash to pay the roughly $1 million tax bill, but balked. So Pence had the client use her RMDs to foot the bill, converting chunks of the traditional plan in several steps. That way, “she didn’t feel like she was using her ‘own money’ to convert,” Pence says.

Advisors don’t like a client taking money out of their traditional IRA to pay a conversion tax bill. Doing so crimps the size of the retirement pot available for future growth. Fidelity Investments says investors should instead use cash from a non-retirement savings or brokerage account. Pence’s RMD method adds another option. “It’s all about that mental strategy,” she says. Clients “fall in love with the idea, because it doesn’t feel like it’s coming out of their pocket.”

Complicated calculus

Taxes aren’t the only issue. A conversion doesn’t make sense if an investor is going to need income from his account in the “near future,” says Ross Bruch, a senior vice president and senior wealth planner at Brown Brothers Harriman. Why? “If you’re going to pay tax either way, you’re better off to have a few additional years of growth,” he says.

A conversion may also not be worth it if an aging investor plans on moving from a high-tax state like Connecticut to retire in no-tax Florida, or Pennsylvania, which doesn’t tax retirement accounts. That’s because there would be no savings on the state taxes owed (the top rate in Connecticut is 6.99%) when transferring a traditional IRA to a Roth.

Already inherited a traditional IRA? Unless you’re the surviving spouse, you can’t convert it to a Roth, writes Debra Greenberg, the director of personal retirement strategy and solutions at Bank of America, the parent of Merrill Lynch. And things get complicated when converting an IRA that contains after-tax contributions.

Legislation passed by Congress in December 2019 known as the SECURE Act boosted the age for starting required RMDs, to 72 from 70 ½. That means investors who are just below that age and likely retired are probably in a lower tax bracket. So locking in that bracket by converting makes sense, writes Dennis Culver, an associate advisor at Insight Wealth Strategies.

The new law also said that beneficiaries other than spouses of retirement plans of all stripes have to cash them out entirely within 10 years of the original owner’s death. Previously, an heir could “stretch” withdrawals indefinitely. The law makes it scary for an adult child to inherit a traditional IRA in her peak earning years, as the legacy would increase her taxable income and potentially push her into a higher tax bracket. But it also complicates consideration for a conversion.

“The SECURE Act has made it more complex and confusing for investors and advisors to understand whether a Roth conversion is a good idea,” says Bruch. “There are so many variables where the outcome is unknown.”