Massive retirement savings aren’t just for venture capitalists who hit it big with Silicon Valley startups.

Many high-earning professionals in corporate America, from doctors and lawyers to executives and airline pilots, can accumulate a seven-figure or more retirement cache of tax-free profits using a loophole known as a mega backdoor Roth conversion.

Those high earners make up a clutch of corporate professionals whose financial advisors know a big secret: that giant IRAs aren’t just for the Peter Thiels of the world. Thiel, a co-founder of PayPal, made headlines in financial circles in June when ProPublica reported that his Roth IRA, seeded with less than $2,000 worth of shares in PayPal in 1999 and later with stock in other fledgling start-ups, like Facebook, was now worth $5 billion.

Bloomberg News

“There’s no reason that a professional who is maximizing their retirement savings every year can’t amass a $5 million IRA over a few decades,” says Justin Miller, a partner and national director of wealth planning at Evercore Wealth Management in San Francisco. “It’s not uncommon to see lawyers and doctors with IRAs in the $5-10 million range.”

Roth plans are funded with non-deductible dollars on which taxes have already been paid. Owners can withdraw the gains without paying ordinary income tax or penalties after they’ve had the accounts for at least five years and are 59 ½ or older.

So how does one transmute a 401(k), the workhorse of the American retirement place, into a pot of gold at the end of the retirement rainbow? The plans are funded with deductible, pre-tax contributions that are invested in stock and bond funds, and owners pay ordinary tax on the profits when they make withdrawals.

The road to that wealth combines two legal tax benefits.

The first is a lesser-known rule in the tax code that allows individuals over age 50 to put extra, after-tax money into their employer-sponsored 401(k). This year, such taxpayers can put up to $64,500 total into their plans, consisting of regular, pre-tax contributions of up to $26,000, plus their employer’s match and additional dollars on which they’ve already paid taxes.

Younger than 50? The still-generous limit, which doesn’t include the $6,500 catch-up contribution, is $58,000, including the maximum $19,500 from the individual. That’s nearly 10 times the $6,000 allowed in annual contributions to a Roth IRA.

The second benefit involves converting a portion of an employer-sponsored 401(k) into a Roth IRA, which then grows free of tax.

Few investors have access to diamond-in-the-rough pre-IPO stock or profits interests known as carried interest that private equity managers hold in companies in which they invest.

But they do have access to their six-figure (or higher) salaries.

While that won’t get them to a billion-dollar Roth like Thiel, it can nudge them into the single- and double-digit millions come retirement.

“A lot of people think it is only for the very wealthy,” says Brett Bernstein, the CEO and co-founder of XML Financial Group, a $1.3 billion RIA headquartered in Falls Church, Virginia. “That’s not true. But it is designed for people who have significant disposable income. Mega backdoor people are making at least $300K a year.”

Say a 55-year-old cardiologist making $460,000 a year — about an average salary, according to Medscape — contributes the maximum $19,500 allowed this year, plus the maximum $6,500 in catch-up contributions for $26,000 total. Her employer, a giant hospital system, matches that $26,000 at 50 cents on the dollar (up to 4% of salary), kicking in $13,000. So the cardiologist has $39,000 in her 401(k). Under IRS rules, she can kick in a further $25,500 in after-tax dollars.

Now our cardiologist converts a portion of her 401(k) to a Roth IRA, which grows free of tax. Don’t touch that IRA for at least five years and wait until you’re 59 ½, and the withdrawals are tax-free.

The “mega” comes from the ability to sidestep the normal income and contribution limits for a Roth and kick in much bigger sums. This year, individuals making less than $140,000 a year ($208,000 if married), can normally put $6,000 into a Roth and $19,500 into a Roth 401(k). The amounts are slightly higher if they’re over age 50.

The “backdoor” comes from sidestepping those same limits when converting a traditional plan to a Roth. The 2017 tax code overhaul blessed that move, creating a path for high-income earners to fund the plans even where their income levels are above the limits.

Conversions of traditional IRAs to Roths are all the rage amid the Biden administration’s proposed tax hikes. What advisors say is less noticed, and not used nearly enough, is the ability of high-earning people with 401(k)s through their companies to juice the amount they convert. A high-paid earner in technology or pharmaceuticals probably changes jobs once every five years or so, according to Alyson Nickse, a partner and wealth manager at Crestwood Advisors, a $4.5 billion RIA headquartered in Boston. That’s a prime time to roll over an old corporate 401(k) into a Roth IRA, she says, and start — or continue — the process of after-tax contributions.

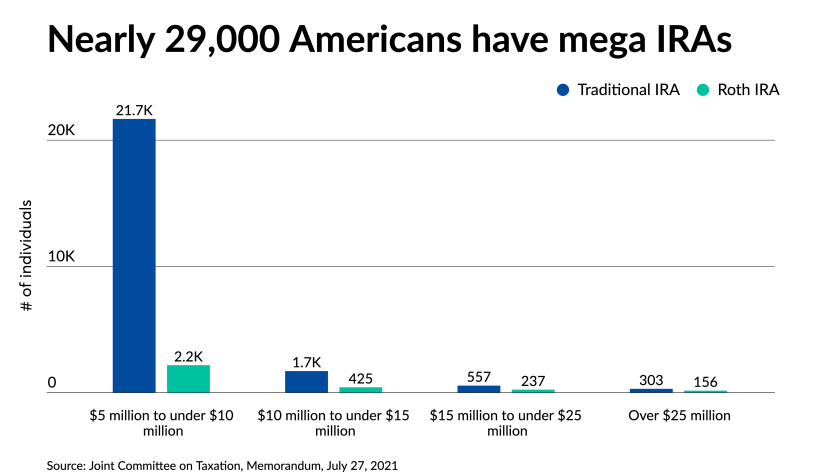

The IRS defines “mega” as a traditional or Roth IRA holding at least $5 million, according to the most recent data from the nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation last month. (Thiel’s is 1,000 times that size.)

How many people have a mega IRA?

In 2019, 2,175 people had Roth IRAs worth between $5 million and less than $10 million, according to the JCT. Meanwhile, nearly 21,700 had traditional IRAs worth that much.

More than 660 people held Roths worth between $10 million and $25 million. Meanwhile, nearly 2,300 owned traditional IRAs worth that much.

Nearly 500 people had an IRA worth over $25 million. One-third of those were Roth plans.

To use the mega backdoor strategy, a high earner has to have a 401(k) that allows extra, after-tax contributions. Three-quarters of employer plans permit that, according to Hattie Greenan, the director of research at the Plan Sponsor Council of America. The plan must also allow transfers to a Roth known as “in-service withdrawals.” Just over half, or 56%, of 401(k) plans allow such withdrawals for reasons other than hardship, Greenan says.

Thiel used cash in his Roth IRA to buy pre-IPO shares in PayPal that he valued at $0.001 a pop. Advisors say his approach carries lots of risks, not least of which is the proper valuing of the shares.

Complex IRS rules state that if an IRA engages in a “prohibited transaction,” all growth in the plan since the transaction becomes taxable at ordinary rates. The IRS outlined Roth transactions that it considers hallmarks of an abusive tax shelter in 2004. Jeffrey Levine, the director of advanced planning at Buckingham Wealth Partners, wrote a technical explanation of the red flags and grey areas for Financial Planning last month.

Truly mega IRAs holding in the upper tens of millions of dollars or more “are not for the mere mortal — they typically require founders share or partner interests,” like Thiel had, says Jonathan Bergman, the president of TAG Associates, an RIA in New York serving high net worth clients.

But garden-variety mortals with large paychecks and leftover money to invest can still get a piece of the action. Bergman cites one client who put half a million dollars in his Roth IRA into the publicly-traded shares of an e-commerce company that was later acquired, turning the pot into $3 million.

Miller argues that with Roth IRAs, the majority of wealthy taxpayers shouldn’t “take unnecessary risk with potential transactions that could violate the law” — especially, he says, when they could “prudently invest in straightforward shares” in an index fund.